Why Do Business Cases Matter

“Ideas are easy. Execution is hard,” as Guy Kawasaki once put it.

But the real challenge in enterprise organizations isn’t just execution – it’s choosing what’s worth executing. Getting that choice right is where the biggest gains – or the costliest mistakes – are made. That’s why business cases matter – they create the discipline to separate promising opportunities from comforting illusions, and to ensure that investments are judged on more than instinct, enthusiasm, or momentum.

This article explores some of the most common business case pitfalls – the ones that look convincing on the surface but quietly drain resources. Recognizing them is the first step in building an investment process that puts substance over gloss.

Business Cases That Can Fool You

The “Sunk cost”

This is the classic trap of throwing good money after bad. Leadership knows the project isn’t delivering, but the idea of writing off the investment feels unbearable, so more funding is pushed in “to get it over the line.” The end result is usually more waste, not a recovery.

Example: A failed ERP implementation that everyone knows should be scrapped, but is kept alive because millions have already been spent.

image:medium

The ”Institutional momentum”

These are projects that keep going simply because they’ve gathered internal inertia. Nobody remembers exactly why they started, but the assumption is that they must be important because so many people and resources are already tied up. In reality, they often limp forward without delivering meaningful outcomes.

Example: A reporting dashboard rebuild that’s been passed between teams for years, never fully launched, but still quietly consuming budget.

The “favorite project”

These are the “go-to” initiatives that an organization repeats every few years despite a poor track record. They provide the comfort of familiarity, but rarely produce tangible results – if it didn’t work last time, why would this time be different? They soak up energy that could be spent on fresher, higher-value ideas.

Example: A recurring sales efficiency review that produces glossy PowerPoint slides but no measurable uplift in performance.

The “executive pet project”

These projects exist because a senior executive is personally invested in them, not because the business case stacks up. With executive sponsorship, they’re hard to challenge – even if they lack strategic alignment or evidence of return. They survive on personality, not merit.

Example: A CEO pushing for a bespoke mobile app because they like the idea, despite the market showing no demand.

The “strat-house lullaby”

Like a lullaby, it’s melodic, familiar, and designed to help executives sleep at night. A strategy consultancy is brought in to validate existing thinking or produce glossy decks that calm nerves, without ever shifting the fundamentals. It feels reassuring in the moment, but rarely generates new insight or lasting value.

Example: Commissioning a big-name firm to “validate” that existing distribution channels are correct, instead of tackling real growth challenges.

The “guaranteed pot-of-gold”

These are enormous moonshots packaged as transformation programmes, promising extraordinary returns. Sometimes they work, but more often they are treated as guaranteed bets simply because the upside looks irresistible on paper. They can drain resources from more balanced, achievable opportunities.

Example: Launching a new spin-off business in a completely different sector, pitched as the company’s “future growth engine.”

It’s important to stress that none of these categories are inherently illegitimate. An executive-driven idea might genuinely unlock value, a repeat initiative might finally land on the right formula, and even a moonshot transformation can succeed if the timing is right. The danger lies in treating them at face value – letting the gloss, the sponsor, or the sheer momentum carry them through without proper challenge.

A strong investment process doesn’t reject these projects outright. Instead, it strips away the veneer, clarifies the real costs and risks, and highlights the opportunity cost of pursuing them over alternatives. With eyes wide open, leaders can make conscious decisions about whether to back them, reshape them, or stop them entirely.

image:medium

Six Principles to Enhance Investment Decisioning

1. From cradle to grave

Too often, a business case is treated as a pitch deck, built to win approval, signed off by the board, and then buried on SharePoint. If you are not holding people to account for what was promised, you are not managing investment, you are wasting it. It is the corporate equivalent of negotiating a supplier contract for months, signing it with fanfare, and then saying, “Just crack on and invoice us whenever.” No one would accept that in procurement, yet it is astonishingly common when it comes to internal investments.

A real business case should live with the project for the entire lifecycle of the initiative. It is not a static document, but a financial profile against which actuals are booked and reality unfolds. When kept live, it forces organizations to confront the sunk cost fallacy, avoid blind comparisons to the original promise, and make conscious choices about whether to accelerate, pause, reshape, or stop.

How to keep it live:

- Keep business cases in the same environment as portfolio reviews. If they only exist in decks, they are already stale. Strategic Portfolio Management solutions such as Kiplot bring the entire portfolio into a single view, so cases cannot be filed away and forgotten.

- Update assumptions, risks, and dependencies as delivery progresses. If they are not updated, the case is out of date and no longer a decision-making tool.

- Anchor every case to enterprise priorities and capacity. If it cannot be weighed against alternatives, it should not be prioritized.

- Put outcomes side by side with spend so reallocation decisions are data-driven, not political.

Handled this way, the business case stops being a one-time approval exercise and becomes an active steering mechanism for where capital and capacity should flow next.

2. Get the governance right

Governance is where business cases either turn into a decision-making tool or a box-ticking exercise. Too often, organizations try to force everything through the same funnel, whether it’s a minor process tweak or a billion-dollar transformation. The result is a governance model that is either bloated and slow, or so light-touch that it fails to protect capital.

The right answer is to configure governance to match the shape of the investment. Small changes should move quickly. Large initiatives deserve more rigorous review and staged approvals. What matters is consistency: everyone knows the rules of the game, and no one gets a free pass because of seniority or momentum.

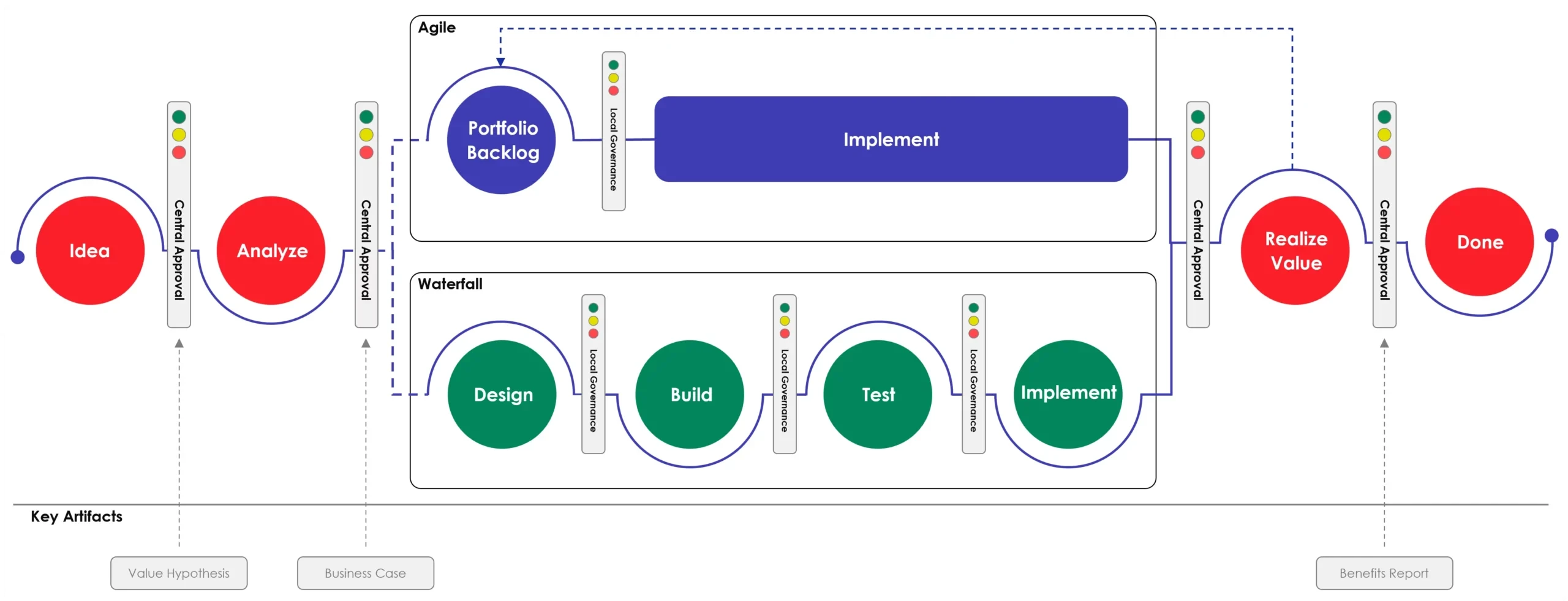

Agile delivery adds another challenge. Iteration and continuous funding don’t sit neatly alongside deterministic waterfall delivery. But that is not an excuse to throw governance out the window. It means you need the right workflows, stage gates, and forums to allow both approaches to coexist. We have included a diagram below that illustrates how you can configure a harmonized workflow that treats waterfall and agile differently. Learn more about this subject in our guide.

Finally, build drawdown into your governance. It is the single most effective weapon against both sunk cost fallacy and pot-of-gold moonshots. Instead of approving one massive cheque at the start, release funding in tranches tied to evidence and outcomes. That way governance is not just about approval, but about ongoing accountability.

💡 The Initial Review – before the organization sinks weeks into spreadsheets and slide decks, put every business case through a quick, high-level review. This early checkpoint gives the investment committee the chance to save time and energy by rejecting weak cases early, sharpen promising ideas by shaping them before the full case is built and protect strategic focus by ensuring only aligned initiatives move forward.

3. Utilize drawdown

Most organizations still fund initiatives like it is 1995: a huge lump sum up front, with the hope that value will eventually materialize. That approach almost guarantees waste, because once money is spent, momentum and sunk cost take over.

Drawdown flips this model. Funding is released in stages, with each tranche contingent on evidence that the initiative is delivering or is still viable. It creates natural checkpoints where leaders can ask: should we accelerate, adjust, or stop?

Take a CRM overhaul as an example. Instead of approving a £10m, two-year programme in one go, governance should release a smaller tranche to fund the first integration pilot with a single business unit. If the pilot works and shows measurable improvement in conversion or customer experience, the next tranche funds expansion to other units. If it fails, the loss is contained, and the organization can stop without burning the entire budget.

This discipline is uncomfortable, especially for executives who want to lock in budget and move on. But it is the most effective way to prevent initiatives from drifting into the “too big to fail” category. Drawdown makes sure money follows outcomes, not promises.

4. Think beyond return on investment (RoI)

Financial return will always matter. It might still be an approval gate. organizations need to know whether an investment pays back. The problem is when ROI becomes the only measure, essential work gets pushed aside.

Resilience only gets attention after an outage. Compliance waits for the fine. New markets are entered too late to matter. ROI-only thinking doesn’t only delay these things – it leaves the organization exposed until failure forces action.

A better business case ties financials to strategy, customer impact, and delivery capacity. It shows how one initiative enables another, where dependencies create risk, and what assumptions the organization is carrying.

That’s the difference between a cost-justification exercise and a tool for choice. A business case should force the organization to make its trade-offs in the open: whether it’s prepared to sacrifice resilience for speed, or delay compliance to chase short-term revenue.

5. Measure what matters

When building a business case, the financial measures you include determine whether decision-makers see your idea as credible. Some are simple, others more advanced, but each has a place. Think of them as a progression – from basic checks through to sophisticated investment appraisal

- Total Benefit – the sum of all expected positive outcomes, usually expressed in financial terms. This might include increased revenue, cost savings, efficiency gains, or avoided losses. It answers the simple question: What do we stand to gain?

- Total Cost – the complete cost of delivering the initiative. That means more than just the project budget – it should cover technology, people, training, change management, and any ongoing operating costs. What do we need to spend?

- Return on Investment (RoI) – a straightforward ratio:

(Total Benefit – Total Cost) ÷ Total Cost. It gives a percentage figure showing how much value is generated for every unit of cost. A 50% RoI means the initiative delivers half as much again as it costs. - Payback Time – the length of time it takes for cumulative benefits to cover the initial costs. If an initiative costs £2m and generates £500k in net benefit each year, the payback time is four years.

- Benefit–Cost Ratio (BCR) – a simple fraction:

Total Benefit ÷ Total Cost. While RoI looks at net return, BCR shows the relationship of gross benefits to costs. A ratio above 1.0 suggests benefits outweigh costs. - Annualised RoI – an RoI expressed on a per-year basis. This helps compare initiatives of different lengths (e.g., a 3-year versus a 5-year initiative) on a common timescale.

- Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) – extends beyond project costs to include long-term operational, maintenance, and even end-of-life disposal costs. Particularly useful for technology-heavy initiatives.

- Net Present Value (NPV) – NPV recognises that money today is worth more than money tomorrow. It discounts future benefits and costs to their present value using an agreed “discount rate.” If NPV is positive, the initiative creates value once the time value of money is accounted for.

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) – IRR is the discount rate at which NPV equals zero. In plain terms, it’s the effective annual rate of return the initiative is expected to generate. It allows easy comparison against other investments or a required “hurdle rate.”

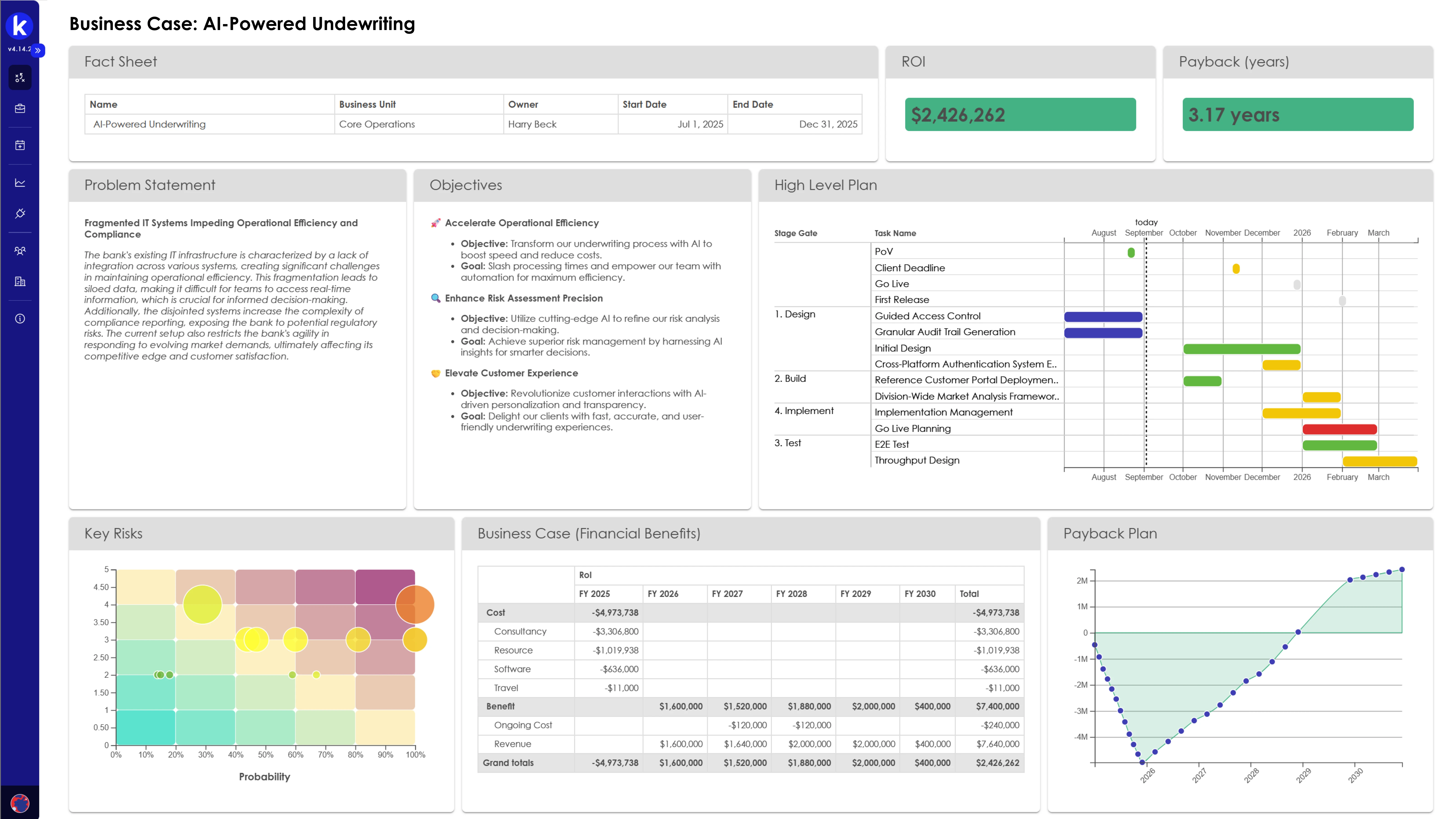

6. The Goldilocks mandate

A strong business case strikes a balance: just enough information to enable choice, but not so much detail that it becomes unreadable. Overly long documents risk becoming political artefacts that only a few insiders will ever examine. Overly thin cases leave decision-makers guessing. The objective is not polish, but clarity.

A credible case makes the fundamentals visible:

- Strategic fit – A clear line to enterprise priorities. Without it, the case has no standing.

- Tangible outcomes – Real impact on customers, revenue, cost base, resilience, or compliance. Milestones are activity, not outcomes.

- Financial clarity – Ranges and scenarios that expose uncertainty. A single number creates false confidence and undermines comparability.

- Non-financial benefits – Measurable contribution to leading indicators such as OKRs or enterprise KPIs. These often provide the strongest signals of progress but are invisible if financials are the only lens.

- Visible risks and assumptions – What could break the case, surfaced early. Risks that remain buried are the ones that derail delivery.

- Governance – Defined ownership and a plan for tracking outcomes. Without accountability, the case lacks credibility.

To achieve this balance, the case must be structured differently. The anatomy of a strong case includes:

- Fact Sheet – Initiative, owner, and timeline. Anchors accountability from the start.

- Problem & Objectives – Why the work matters and how it links to priorities. Filters out sponsored ideas that sound appealing but do not advance strategy.

- Critical Success Factors – The conditions that must hold true. Prevents fragile initiatives from progressing on promises that will not survive delivery.

- Business Case & Payback – Costs and benefits over time, shown as ranges. Creates comparability across initiatives instead of pretending to certainty.

- Spend Profile – Where the money actually goes. Tests whether capital is directed to the right areas or spread too thin.

- Risk Grid – Dependencies and potential failure points. Keeps risk visible and part of the decision-making process.

The value is not in the number of pages but in the quality of visibility. A Goldilocks case provides the right level of information to assess initiatives consistently, balancing financials with non-financial signals. Done well, it becomes a live tool for directing capital and capacity, not a static document filed away after approval.

Role of Strategic Portfolio Management

A business case, even when built well, is still just one perspective. The real decisions aren’t about a single case – they’re about which work to back across the whole portfolio. That’s where traditional processes fail: cases live in decks and spreadsheets, judged in isolation, and strategy drifts while capital stays locked in the wrong places.

Strategic Portfolio Management changes that. It puts every case into a single system where they can be compared, tested against shifting priorities, and revisited as conditions change. Instead of approving work once and hoping for the best, organizations gain the ability to reallocate capital continuously and keep strategy moving.