Most of us understand that correct allocation of capital expenditure is critical, but surprisingly few of us (outside finance!) understand “why”. In this article we’ll look at 3 key reasons why it’s important for your organization, in layman’s terms.

We’ll do our best to avoid the jargon, no accounting qualifications required!

What is CapEx?

CapEx is the common abbreviation for Capital Expenditure. In any organization, spend is categorized into two buckets, CapEx (capital expenditure) and OpEx (operating expenditure). There are complex, detailed standards published by national authorities (e.g. FASB, FRC, IFRS) that dictate how organizations may account for CapEx and OpEx. But if we keep it simple for the purposes of explanation, we can think of CapEx as costs associated with changing the organization, building new things and transformative projects – it is investment in the future (not the present) of the organization. OpEx on the other hand describes costs associated with running the organization. As a deliberately simplistic rule of thumb, an organization should be able to “turn off” all CapEx expenditure without immediate impact to any business operations.

This is why fixing bugs in production software is generally considered “OpEx” whereas building new software is generally considered “CapEx”.

So why is this important?

Reason 1: Better financial health

What does this have to do with my timesheet?

The value of the time you spend working on projects can be directly added to the balance sheet of the organization – this is a key component of the organization’s market value. For someone earning $100K who capitalizes 80% of their time, that could add $80K to the organization’s balance sheet*.

*There are some significant caveats here that we’ve deliberately brushed over for the sake of simplicity. Read on to learn more about depreciation and amortization.

How is this possible?

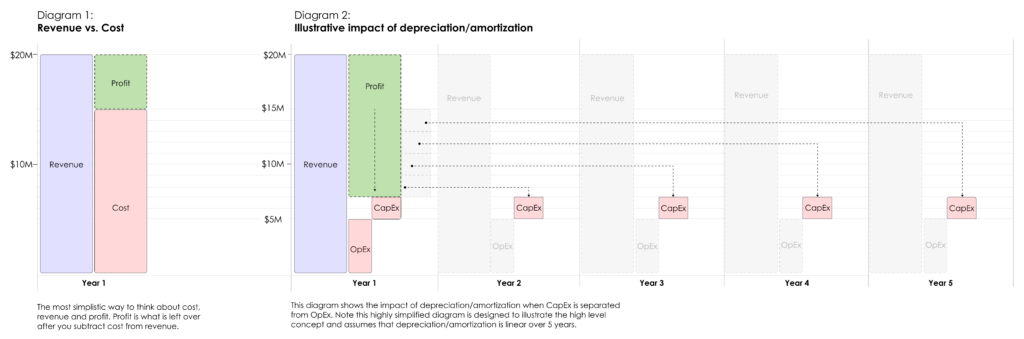

When an organization incurs cost for something that's benefit will last beyond the current year, it is generally considered to be an asset. A small example of an asset would be a laptop used by a member of staff. If we assume the laptop will be used for 3 years, the laptop would be listed as an asset owned by the company for this period of time. The total value of all assets is listed on an organization’s balance sheet, which essentially describes the total value of everything the company owns.

However, not all assets are tangible, and not all assets are purchased. An example of this might be a mobile app built by an organization for its customers. In simplistic terms, if the total capitalizable value of all the time sheets submitted by resources to build the mobile app totals $10M, the organization can record the value of this asset (the mobile app) on its balance sheet. This better reflects the value of the organization. The cost incurred to build the mobile app will generate significant value over the coming years, and should be recognized as a valuable asset.

If teams fail to correctly attribute their time to the build of this asset (the mobile app), the organization will not be able to add this to its balance sheet, potentially leading to undervaluation of its assets

Reason 2: Improved “core profitability”

What does this have to do with my timesheet?

If a team of 10 people costs an organization $1M over a year, 100% capitalization of these costs could “add” $1M in core operating profit to end of year metrics.

How is this possible?

The capital expenditure that an organization is making at any given point in time is crucial for investors and other market stakeholders to gauge the financial health of the organization. An organization may describe its “core operating profit” by subtracting its OpEx from its revenue. This means the organization can exclude CapEx expenditure from this metric. It’s worth noting that “core operating profit” is an example of non-standard, but commonly used terminology to describe the financial performance of an organization.

For example, in the years after 2008, as the financial services industry undertook massive reform, we heard banks reporting multi-billion dollar losses, but CEOs often positively describing the health of the “core business” as highly profitable to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars. In 2010, NatWest (UK) announced a ~£1B total* loss, but an operating profit of ~£2B. This is the difference between capital expenditure to restructure and transform, versus the cost to actually run the business.

The implication to investors is that hypothetically, at some point in the future, the organization might choose to reduce its capital expenditure, and enjoy the profitability of the underlying core business.

*We’ve used the word “total” here instead of “attributable” to minimize jargon.

Reason 3: Increased cash management flexibility

What does this have to do with my timesheet?

Capitalizing more of your time gives your organization greater flexibility for cash planning which can be critical to help it invest more aggressively.

How is this possible?

Unfortunately, we’re going to have to deal with some jargon here – namely depreciation and amortization. Depreciation describes the way certain costs can be “spread out” over time to better represent their impact to the organization. To take a small scale example, many organizations will give portable computers (laptops) to their staff. The cash cost required to buy the laptop is incurred on the day it is purchased. But the laptop itself is used (let’s say), for 3 years. If an organization of 1,000 people refreshed all of its computers on 1st January of year 1, it would not be a useful representation to say that the cost of computers to the organization was 0 in year 2. Instead, we use depreciation to spread the cost out over time to better represent how the assets (computers in this case) bought by the capital expenditure enable the business to create value. This would mean we spread the cost of the computer across its 3 useful years. If the computer cost $1,200, we would account for $400 in each year. For the avoidance of confusion, the $1,200 is still paid in cash terms on the day the computer is bought, but the “cost” ($400/year) is accounted for over the 3 year period.

Depreciation is the name of the method used to “spread the cost” of tangible assets. These are things we can touch, like a computer in the example above. Amortization is the same concept, but applied to intangible assets. These are things we can’t touch, like a mobile app.

If an organization were to spend $10M of capitalizable internal resource time building a proprietary mobile app, we can amortize this cost over the mobile app’s useful economic life. Useful economic life describes how long the asset will generate value for the organization. Let’s say, for the purposes of our example, the useful economic life of our mobile app is deemed to be 5 years. That means we could spread the cost over the 5 years at $2M per year. Capex typically carries beneficial tax treatment, though the exact treatment is subject to complex regulations that vary between jurisdictions.

Why does “agile” make this harder?

Agile necessitates an acceleration away from traditional operating models in which some teams in your organization are “change” and some are “run”. The teams who fix the mobile app when it goes down are often the same resources who build the new features. This makes tracking capital expenditure less straightforward, but no less important. For many organizations, it’s going to make time tracking more critical as we can no longer point at entire teams and say – “this is capital expenditure”. Organizations must get better at differentiating different types of costs at a more granular level of detail.

Learn more about the key principles of tracking time in agile organizations with our guide.