Understanding the Two Models

In any organization delivering change, resource planning is about answering a deceptively simple question: do we have the people we need to deliver the work we’ve committed to? The answer depends on how that work is structured. Traditional or “waterfall” delivery and agile delivery take fundamentally different approaches to planning capacity. Understanding those differences is essential to managing today’s complex enterprise portfolios.

Waterfall Resource Planning: Taking the People to the Work

Traditional resource planning starts with the project. A piece of work is defined, scoped, and budgeted. Once that structure is in place, people are assigned to fill roles. Resource managers look across the organisation to find individuals with the right skills and availability to be allocated to the project.

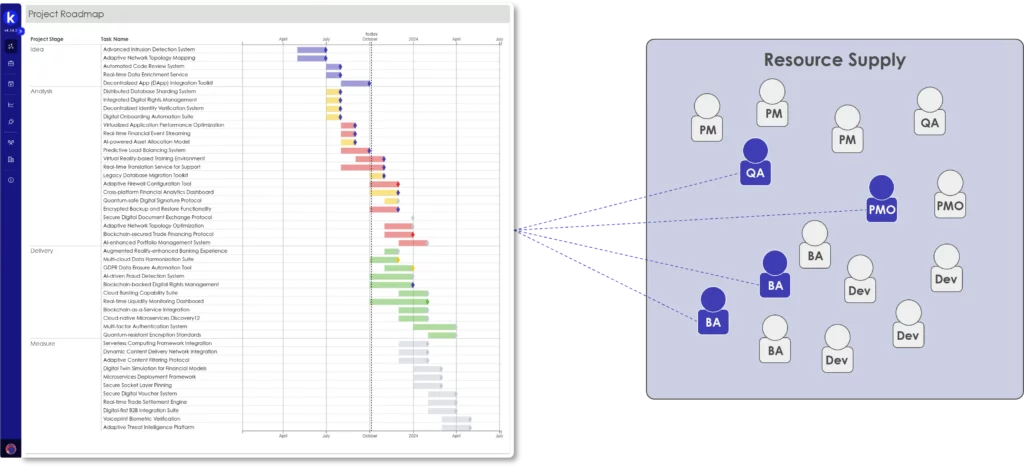

The diagram below illustrates traditional resource capacity planning.

image:borderless

This approach treats people as units of supply. If someone is available and has the right skill set, they can be picked up and assigned to a new project. After that project ends, they can be reallocated elsewhere.

This model is straightforward to understand and aligns well with how most finance and reporting structures are set up. It enables detailed resource forecasting and cost attribution based on specific project codes. But it also has trade-offs.

One of the most significant trade-offs is ramp time. When people are brought onto a new project, it takes time for them to get up to speed. They need to understand the context, build relationships, navigate new ways of working, and find their rhythm within the team. Similarly, as a project nears completion, there's a wind-down period where velocity drops as people start shifting attention to their next assignment.

As a result, many projects only operate at their peak effectiveness between 60 to 80 percent of their lifecycle. The rest is spent ramping up, ramping down, and managing the transitions. This might not seem like much on a single initiative, but at enterprise scale, this dead time becomes massively expensive – both in terms of cost and lost momentum.

💡 Most traditionally delivered projects only operate at their peak effectiveness between 60 to 80 percent of their lifecycle.

image:borderless

There’s also a deeper cost. When people roll on and off different projects frequently, it becomes difficult for them to build deep expertise in any one domain. The institutional knowledge that organizations so badly need – what works, what doesn't, how things really operate – can become scattered. This is particularly true in knowledge-heavy environments like software engineering or large-scale change delivery, where nuanced context often makes the difference between success and rework.

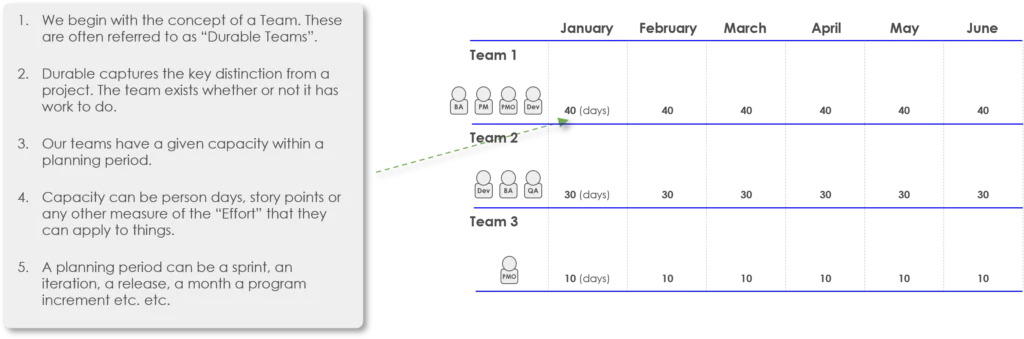

Agile Capacity Planning: Taking the Work to the People

Agile planning flips this logic. Instead of forming a new team around each new initiative, agile organizations invest in stable, cross-functional teams that stay together over time. These teams are the fixed engines of delivery. New work is broken down, refined, and prioritized – then routed to the teams best equipped to handle it.

This is much more like running a restaurant kitchen. You don’t hire a new chef every time someone orders a meal. You have a trusted kitchen crew that works together every day. They know where everything is. They understand each other's strengths. They have intuition about which dishes are more complex and which ones can be turned around quickly. And, critically, they improve over time – not just at cooking, but at cooking in this specific restaurant. They understand what menu combinations work, what the regulars like, and how to adapt when there’s a rush.

💡 Critically, they improve over time – not just at cooking, but at cooking in this specific restaurant

That accumulated knowledge is one of the biggest benefits of agile planning. When teams stay together, they develop velocity, shared context, and the ability to self-organize around problems. Instead of re-estimating who is free every time a new request comes in, you estimate whether the work fits into the capacity of your existing teams – and if not, whether new teams are needed.

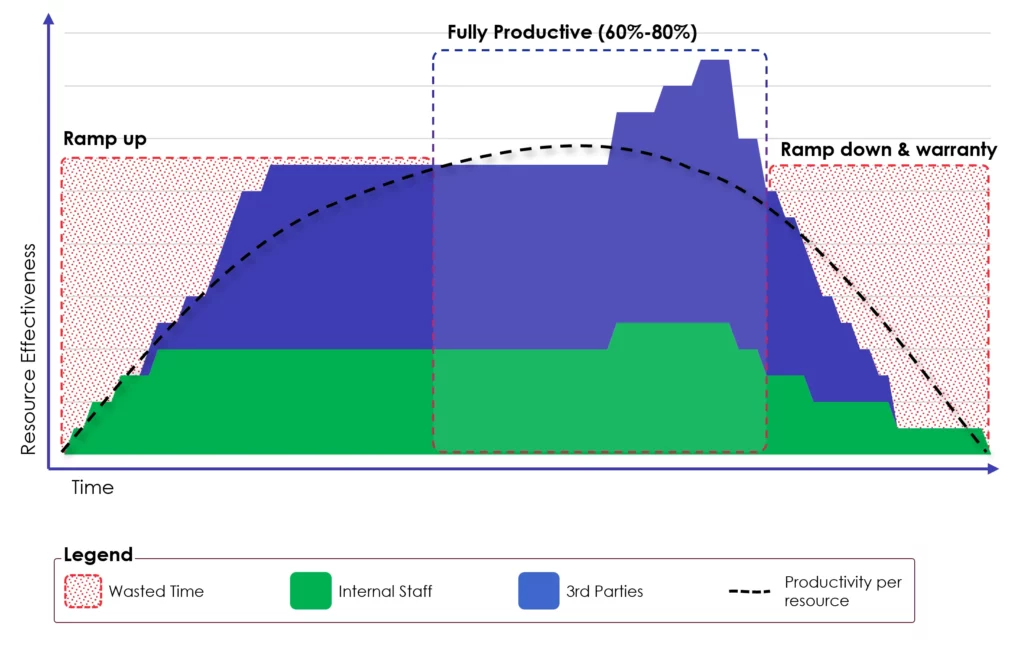

How Agile Team Planning Works

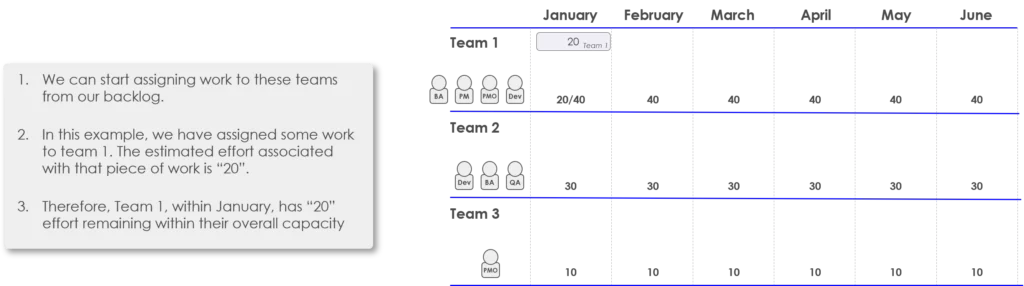

Agile capacity planning typically involves the following steps:

- Define stable teams. Each team has a known capacity (measured in story points, hours, or another unit). Their skills are well understood, and they stay together over time.

- Refine new work into deliverable chunks. This often happens through a backlog grooming process. Work is clarified, sized, and shaped to fit team capacity.

- Match work to teams. Based on skills, availability, and business priorities, work is assigned to the most suitable team -not the other way around.

- Sequence based on capacity. Teams commit to what they can deliver in a sprint, increment, or planning period. If something won’t fit, it is re-sequenced or deprioritized.

This model prioritizes flow and throughput over short-term utilization. It assumes that well-formed teams can deliver more value consistently than a rotating pool of individuals who are constantly switching context.

Step 1:

image:borderless

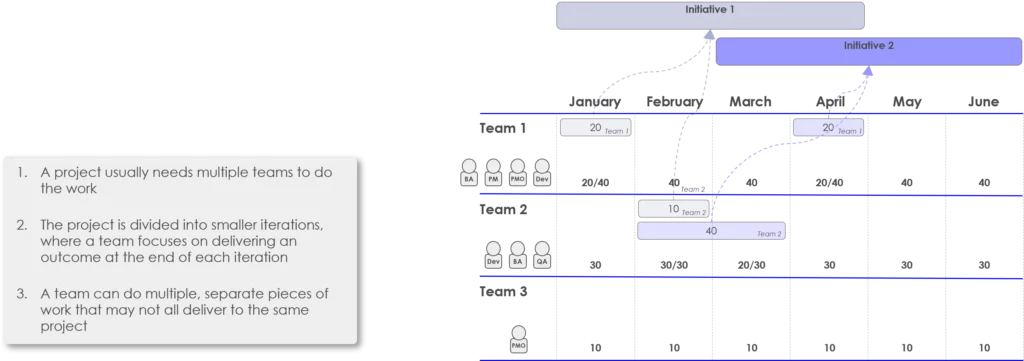

Step 2:

image:borderless

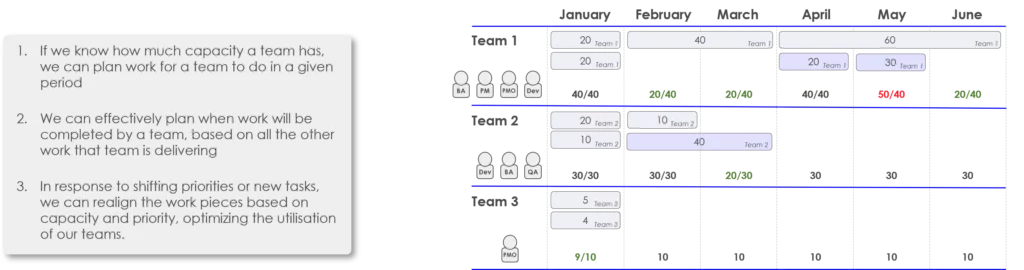

Step 3

image:borderless

Step 4

image:borderless

Pros and Cons of Agile vs. Traditional

| Aspect | Waterfall Approach | Agile Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Core unit of planning | Individuals | Stable teams |

| Capacity logic | People are allocated to work | Work is allocated to teams |

| Predictability | Easier to forecast at the individual level | Easier to forecast at the team level |

| Flexibility | High flexibility to assign specific people to specific tasks | High stability, but requires grooming and sequencing |

| Expertise depth | Shallow unless the same people are repeatedly assigned to the same domains | Deep expertise built over time within teams |

| Overhead | High coordination cost in large portfolios | High upfront investment in team formation and backlog discipline |

| Financial alignment | Naturally aligns with cost attribution per project | Requires different models for cost attribution and tracking |

Making the Models Work Together

In the real world, most organizations don’t choose one or the other—they operate both. Some departments work in agile teams, while others continue to deliver through traditional projects. That hybrid reality creates tension, particularly around resource forecasting and portfolio planning.

There are two common ways to manage this tension.

Option 1: Parallel Resource Pools

The simplest and most scalable model is to maintain two clearly separated resource pools.

- Agile resources are grouped into long-lived teams. These teams have fixed capacity, and work is planned against them through backlogs. Forecasting is based on team throughput and prioritization.

- Waterfall resources remain outside these teams. They are assigned to projects in the traditional way, based on availability and skill fit.

This model works because it maintains clarity. The rules of the game are different for each group, but they are applied consistently. Portfolio planners can roll up data across both streams and make trade-off decisions without trying to force one logic onto the other.

Option 2: Hybrid Assignment

In more complex environments, some individuals may contribute to both waterfall projects and agile teams. This sounds flexible, but in practice it is difficult to manage well.

In this model, someone might belong to an agile team with 60 percent of their capacity, and be assigned to a waterfall project for the other 40 percent. On paper, this seems like a good way to stay efficient. In reality, it creates constant conflicts:

- The person’s time becomes over-scheduled or under-scheduled depending on shifting project demands.

- Agile teams struggle to commit to work when capacity is unreliable.

- Resource planners are forced into continual reconciliation exercises, often in spreadsheets.

The more this model is used, the more effort it takes to manage. Without strict guardrails, it creates a hidden industry of middle managers who spend their time smoothing over the consequences.

Final Thoughts

The question is not whether waterfall or agile planning is better. The more useful question is: where in your organization does each model make the most sense, and how will you manage the interaction between them?

By understanding the core differences – and being deliberate about how you structure your resource pools – you can get the best of both worlds. Consistent team-based delivery where it drives the most value. Traditional allocation where it is necessary. And clarity at the portfolio level to make confident decisions across both.